Mayor Elliott and Councilor Mercier have placed the following motion on the agenda for Tuesday’s City Council meeting:

M. Elliott/C. Mercier – Req. City Council vote to revert Fr. Morrisette Blvd. back to a four-lane traffic through-way and remove bike lanes.

For a description and lovely photos of the bicycle lanes in question, installed last August, see Marianne Gries’s Art is the Handmaid blog. A Lowell Sun story[1] provides comments from the councilors as to their reasons:

Mayor Elliott said, “We have enough traffic congestion problems, we don’t need to create any more,” and opined they were a safety hazard for motorists.

Councilor Mercier said, “Everywhere I go, people are so upset about it,” and suggested right-turning drivers may crash into a car improperly driving in a bicycle lane. She regrets prior support of the lane reduction.

For me, one quote of Mayor Eliot’s stood out more than any others, “The intent should be to move vehicles in and out of the city.” Moving vehicles “in and out” is only one of many goals of a good transportation system. Not only are cities across the US embracing these other goals, but they are also getting positive results. Lowell has described its goals in community plans, and data-driven decisions may be able to assist in achieving that vision.

What are our Goals?

Goals of a transportation system include the safety of all users of the system, economic vitality, promoting quality and health of life, and increasing access to destinations. The system must be economically and ecologically sustainable. It should also be just: providing for those who cannot drive. I’ve adapted these goals from the US Department of Transportation’s strategic plan.

We do not need to look to US DOT for goals, however. Lowell has set its own goals in local planning processes. In Sustainable Lowell 2025, the first goal listed under “mobility and transportation” is to promote bike and pedestrian mobility, and the first action under that goal is:

Develop, implement and identify funding to maintain a citywide Bicycle Plan that continues to build upon the existing network of bike lanes, sharrows (shared use lanes), storage racks, and signage.

This builds upon years of public outreach. To take two examples, student focus groups that were part of the 2010 UMass Lowell Downtown Initiative Report suggested safer options for bicyclists including bike lanes linking campuses and downtown; and in 2009 Hamilton Canal District neighborhood outreach, all the downtown neighborhoods asked for bike improvements, with the Acre specifically suggesting “clearly-marked bike lanes.” In a 2012 Sun article, former City Manager Lynch said, “More than two-thirds of residents surveyed identified bicycle infrastructure as a key opportunity for improving the city’s transportation network.”

What about Cars?

Even if Lowell’s only goal was moving vehicles in and out of the city, Father Morissette’s importance in this is negligible. Partly because it was originally envisioned as part of an extended Lowell Connector, it was built wider than necessary: 65’. However, it is only one of several east-west routes connecting downtown to highways. Its importance is as a piece of a redundant network, not as a major thoroughfare. Father Morissette’s role is evidenced by its relatively low average daily traffic: In 2011, approximately 9,000 cars per day near Aiken Street. For comparison, Dutton Street near Lord Overpass was approximately 32,000 average daily in 2007.

Because of its low traffic, Father Morissette provided an excellent opportunity to provide additional parking to the Wannalancit Mills and Tremont Yard developments and a bicycle lane that could connect UMass Lowell’s north campus with downtown. In a February 26, 2013, City Council meeting, Adam Baacke provided data that Father Morissette was only 50-75% utilized with four lanes, and the it would be at only 80% capacity with two fewer lanes.[2]

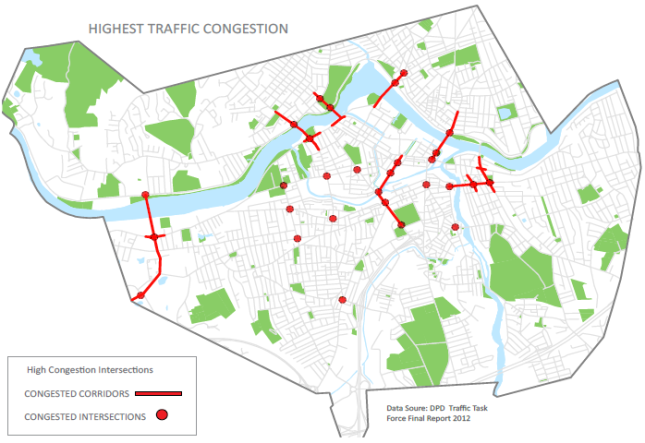

A 2012 map by the City’s planning department shows key concern areas at river crossings, near Lowell Connector, and a few key N-S routes.

This follows Federal Highway Administration research showing that a reduction of lanes for streets with under 20,000 average daily traffic does not create an increase in congestion. This is because cities usually provide a left-turn lane, letting cars waiting for a turn “get out of the way” of straight traffic. Father Morissette’s median makes providing these lanes at intersections difficult without reconstruction. Instead, right turn lanes have been provided. This increases the safety for bicycles (cars aren’t making the turn into them) but doesn’t significantly ease congestion – and may be one reason cars illegally use the bicycle lanes to pass left-turners. However, it appears much more likely that a lack of through-capacity does not cause Lowell’s congestion problems. Rather, intersections near Lowell’s bridges cause backups, especially along the VFW highway.

To summarize, given its low traffic counts, any congestion on Father Morissette is created not by its number of lanes, but by intersection problems elsewhere in the grid. In fact, keeping the number of lanes to two may reduce difficult merging when Father Morissette turns into the two-lane Pawtucket Street. If this issue stays active, I hope to talk to the City to learn more about its traffic patterns and plans for mitigation.

Road Diets

There are other benefits to a reduction in Father Morissette lanes beyond extra space for parking and bike lanes. Planners call a reduction of lanes to calm traffic a “Road Diet.” The Lowell experience seems to mirror what the research has borne out:

- Speeding has been reduced. Many pedestrians and bicyclists have noted that prior to the lane reduction, Father Morissette was more like a divided highway than an urban street, and motorists treated it as such, breaking the speed limit.

- Crossing is now easier and safer. Two lane streets are shown to have fewer pedestrian crashes than three-lane, both because it’s a quicker cross and because there is no threat of a moving vehicle passing a vehicle that had stopped for a pedestrian.[3]

- Walking along the street is more comfortable. A bicycle lane and parking provides a “buffer” between moving traffic and the sidewalk. Although pedestrians may choose other routes than Father Morissette, many choose the street for public safety reasons: it’s well-lit with plenty of “eyes on the street.” A calm street serves those pedestrians.

Given these extra benefits, the discussion shouldn’t only involve bicycle and automotive safety, but also pedestrian safety and comfort.

Confusion, Education, and Enforcement

A car parked over the buffer on Father Morissette. Some argue lane design is at fault, others may argue for consistent enforcement.

This week’s motion follows last week’s motion requesting a report on bicycle lane laws and fines. The Police Superintendent’s response states that the “recently installed bicycle lanes… have been a source of confusion for the motoring public and a source of frustration for the bicyclists that use them.” It explains that cars can only enter the bicycle lane at intersections (where the solid white line becomes dashed) or when entering/exiting a parking space.[4]

Solid lines almost always indicate a car is not supposed to cross, regardless of whether they are for bike lanes or for other purposes (for example, on highways in construction zones with no passing, the dashed white line becomes solid). This is important design language all motorists should understand. The confusion indicates a greater need for education and enforcement of traffic laws. I might speculate that the poor condition of the lane markings on Lowell’s older streets feeds general confusion about traffic laws.

2013 Lowell Bike Safety Rodeo, courtesy Lowell General Hospital. Open Street Ciclovias could complement this event.

However, others have noted that bicyclists also do not follow traffic laws. A discussion on Lowell Live Feed included ideas that bicycle education and promotion could be a part of creating a bicycle-friendly Lowell. Lowell already has an annual back-to-school “bike safety rodeo,” and MassBike offers classes and workshops on urban bicycling that seem to take place in the Boston metro.[5] Some suggested bringing back Tour de Lowell, a bicycle race for adults and children that took place in the 1990s.[6]

I love the idea of “Open Streets” events, in which one street is closed to vehicular traffic and “opened” to pedestrians, bicycles, and other non-motorized transportation. This type of event has become popular in cities around the world, including cities as large as Chicago and as small (or smaller than) Fargo, North Dakota. A less-traveled lane may be closed to bring attention to the businesses along that street, and safety and educational events may be organized around it. Typical sponsors include health organizations, cycle clubs, and business groups. Perhaps Massbike could offer technical assistance.

Of course, Police officers also play a role in pedestrian and bicycle education and enforcement, and I hope to talk to the Lowell Police Department about their policies soon.

Poor Design of the Bicycle Lanes?

Some have complained that the bicycle lanes were designed poorly: they shouldn’t be in a place that makes bicyclists vulnerable to being hit by open car doors, they should be painted green, they shouldn’t be so wide, and many other criticisms.

In this case, I looked at National Association of City Transit Official (NACTO)’s comprehensive Urban Bikeway Guide, recently adopted by Massachusetts as their bikeway design standard manual. Father Morissette has a 4’ bike lane with an approximately 2’ buffer on both sides marked by double white lines. NACTO standards for a buffered bike lane, include a minimum of 18” buffers, double white lines, treatments at intersections, and a minimum of 5’ (including buffers) to avoid doors from parked cars. It advises wider lanes when possible. The lanes fit within the NACTO standards.

The westbound bicycle lane shifts to the median to avoid the Pawtucket Street intersection. NACTO’s standards handle this scenario, too. Nevertheless, the shift may create confusion, especially with construction in the area.

There are additional optional treatments, such as green paint at each intersection (or along the entire path), diagonal strips in the buffer, or bollards separating the car traffic from bike lane. Some cities have even used the parked cars as a buffer from traffic. Any of these treatments might reduce confusion over whether the bicycle lanes are for cars.

However, each of these has an associated capital and maintenance cost. This cost must be considered against the cost of maintaining all the other lane markings in the City. In addition, the City has long-term plan to reconstruct Father Morissette, possibly with a trolley median, as outlined in the Jeff Speck Downtown Evolution plan. The parking kiosks can be reused on the new street if this happens, but expensive paint and curbing might not be.

What Now?

If you have an opinion, contact the City Council before the meeting! Planner Jeff Speck mentioned the following in an interview with Streetsblog:[7]

…The biggest mistake cities make is to allow themselves to effectively be designed by their director of public works. The director of public works, he or she is making decisions every single day about the width of streets, the presence of parking, the question of bike lanes. And he’s doing it in response to the complaints he’s hearing. But if you satisfy those complaints you wreck the city.

A typical public works director doesn’t think about “What kind of city do we want to be?” They think about what people complain about, and it’s almost always traffic and parking.

The one thing we’ve learned without any doubt, is the more room you give the car the more room they will take and that will wreck cities. Optimizing any of these practical considerations — sewers, parking, vehicle capacity — almost always makes a city less walkable.

This is why it may be helpful for residents to let councilors know that they have a positive vision for the City. Click here to Contact the City Council. I suggest writing, and then registering to speak and attending the Tuesday meeting if you are able. Writing beforehand gives councilors time to think about your comments before their vote.

Residents who support the plans Lowellians made together in visioning sessions must show that support. This is because complaints never go away: I have heard complaints about parking and panhandling in some amazing, vibrant, successful downtowns. These downtowns were successful because they listened and responded to the complaints, but also never stopped working toward the positive vision.

If we, as a community, determine there is a traffic or (non-immediate) safety problem, instead of a quick reaction, a re-examination of bicycle plans might be in order. Boston has an excellent public plan indicating primary bike routes and appropriate treatment for each. We may decide that the City should implement a different design the next time Father Morissette is resurfaced or we may decide to add more paint to the road. Regardless, we would use good data and best practices, and we would objectively measure the results against our collective vision.

Notes

[1] As noted by Marianne Gries, the article stole an image from the Art is the Handmaid blog. ↩

[2] Thanks to Jack at Left in Lowell for posting a short summary of the meeting along with his critiques: Motion To Delay! Oh Frabjous Day! Callooh! Callay!’ ↩

[3] It’s interesting to note that the major finding from that study is that crosswalks without other treatment have little impact on pedestrian crashes for a variety of reasons. ↩

[4] The memo from Superintendent Taylor suggests the width of the current roadway, and therefore the width of the buffers between the bike lane and the driving lane, motorists may believe that there is a bicycle lane within a driving lane. It’s possible motorists are confusing the lane with “sharrows,” which are bicycle icons painted on roads on which bicycles are likely to be travelling. Sharrows don’t actually indicate a changed traffic pattern, as Massachusetts state law allows a bicycle to use the entire lane of a roadway when it is required for safety. The sharrow is only there to remind motorists of this fact. ↩

[5] Thanks to Lowell Live Feed Forum commenter Marianne Gries. ↩

[6] Thanks to Lowell Live Feed Forum commenter Marie Storm Sheehan. ↩

[7] Thanks to Left in Lowell commenter Brian for reminding me of the relevance of this interview to today’s issue. ↩