You may have noticed that we haven’t posted too many articles lately. Part of the reason is that we’re involved in few community initiatives, including “DIY Lowell.” Now that the DIY Lowell website is up and running, we wanted to share our story.

DIY Lowell is an initiative to try to capture all the ideas for projects and events people have and help them make those ideas a reality. For example, someone may have an idea for a temporary art exhibit, share it on Facebook, and then forget about it. We want to help connect that person with an artist, with someone who knows how to get the permits, and with some funding.

DIY Lowell is an initiative to try to capture all the ideas for projects and events people have and help them make those ideas a reality. For example, someone may have an idea for a temporary art exhibit, share it on Facebook, and then forget about it. We want to help connect that person with an artist, with someone who knows how to get the permits, and with some funding.

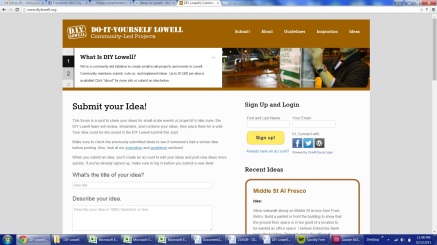

We’re doing this by inviting everyone to share ideas on a forum and in dropboxes around town until June 15. On June 20 until the end of June, the ideas will be up for a vote by anyone who registers for a summit. Our goal is to narrow down the ideas to a small handful that summit attendees would be interested in working on. We have a few guidelines: ideas can’t be expected to cost more than $1,000, they should be completed by the end of the year, they have to relate to space open to the public, and they can’t be illegal.

On July 9, the summit will gather DIY Lowell participants and organizational partners to create action plans for the ideas. A number of very talented folks have volunteered to lead breakout groups about each winning idea, and many organizations have pledged to attend the summit to offer their suggestions on how to kick the ideas off. Citizen working groups formed at the summit will move the ideas forward.

What about after the summit? Well, most exciting, we’ve identified some funding, and we are moving forward with some other fundraising ideas soon. In addition, we’ll keep track of all the projects and offer a helping hand when necessary, connecting those citizen working groups with the help they need.

Why are we doing all this? It’s not just to put a few projects into action, but also to identify the common barriers our working groups face. We’re interested in bringing more voices into the community conversation and encouraging folks who might not have time for a huge commitment to take on a small piece of a small project.

The DIY Lowell Story

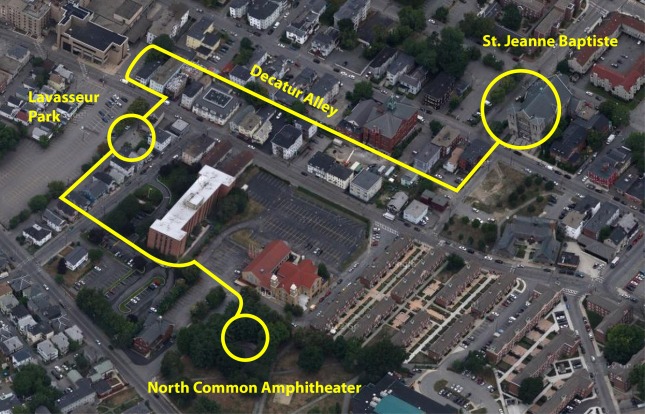

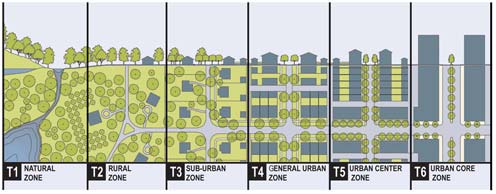

The genesis of DIY Lowell was actually in Buffalo, during the Congress for New Urbanism Annual Meeting. One of the most exciting conversations at the conference was about “tactical urbanism” and “lean urbanism.” The idea is that activists or planners can make short-term, sometimes temporary projects that actually change the urban form long-term. This includes anything from making a parking spot into a mini-park, putting pop-up stores and displays in empty storefronts, and guerilla gardening.

This inspired Aurora and I to come up with a few ideas of our own for Lowell. We thought some chalking or painting of the concrete jersey barriers across from our apartment would spruce up Bridge Street. We talked about a trail that would lead from the National Park Visitor Center to the Boott Cotton Mills Museum just like a small version of the Boston Freedom Trail. However, the more we talked, the more we realized that there could be something bigger than just a project or two.

We were really impressed with the number of Lowell folks who came and participated in the “Transform Mill City” initiative. This series of meetings hosted by a student from UMass Lowell allowed more than forty participants to each meeting to share ideas on giant sticky notes on walls or tables with questions such as “What events would you like to see in Lowell that aren’t here already?” Some popular ideas were a “Firewater” display on the canals and a series of art events or markets.

This wasn’t the only idea-generating initiative in Lowell. The City spearheaded Neighborland a couple of years ago, and it collected ideas via an online website and stickers on an empty downtown storefront. Ideas included an independent theater, free downtown wifi, an expanded Farmer’s Market, and even bocce courts.

What if, however, we combined the two ideas? In school, I ran an organization that accepted project proposals and offered technical support to villages and towns too small to have their own planning departments. There’s a lot of expertise in Lowell already, and we could connect that expertise to these great ideas that sometimes seem to fizzle away. It could be democratic, where the most popular ideas are the ones that get the most attention.

That’s when we started meeting with a lot of people. It’s amazing how many people you can meet with when you’re trying to talk to every group that could be interested in the effort. I started with Yovani Baez, the City of Lowell Neighborhood Planner. She suggested meeting with a few more people, and those folks suggested others, and it soon snowballed. I had to make an excel spreadsheet with the people I met, the people they suggested to talk to, and the ideas on how we could execute our plan.

All in all, Aurora or I emailed or talked to nearly 70 people in the City before we finalized our pitch, including people from the City of Lowell, E for All, Lowell Parks and Conservation Trust, Coalition for a Better Acre, Made in Lowell, COOL, Greater Lowell Community Foundation, Lowell Makes, all the neighborhood groups, a few churches, and a lot of other organizations and groups. During that time, we even took a tactical urbanism tour of the Acre with ACTION.

Each interview helped us form our idea. Just to think of a small handful of examples: Marianne Gries told us to make sure our website was smartphone-compatible for those without computers; Souvanna Pouv suggested doing interviews on LTC shows to market the idea; Geoff Foster reminded us to use examples in every neighborhood in Lowell; Sean Thibodeau recommending throwing an event on a weekday, not a weekend.

We created a mock-up to get feedback from our advisory committee, and with help from the community, we made it into a real webpage

Do-it-Ourselves Lowell

Although we kicked off DIY Lowell, we could never have done any of it alone.

I have to credit Aurora with coming up with the name “Do-it-Yourself Lowell,” or DIY Lowell for short. Her idea was that the organization was all about people feeling like they could take ownership of their city through these small, achievable projects. These ideas aren’t that hard or expensive to put into practice, but most people don’t have the tools, time, or contacts to make their ideas a reality on their own. We hope DIY Lowell will really let people do-it-themselves together.

A lot of others offered invaluable help as well. We’re finding volunteers through the Merrimack Valley Time Exchange, CBA is providing assistance with fund management, a local blog is hosting our website, and we may even be able to hold the DIY Lowell summit in a really cool community space for free. We’re amazingly indebted to our Steering Committee who helped us through decisions such as when to do fundraising, what guidelines to put in place for projects, and how to set up our website.

With all this time invested, you may be wondering why we personally are doing all this work. In a word, it’s fun. We’ve met so many people and we’re hoping to add to what we see happening in Lowell already: a sense of excitement and possibility. It’s a lot better than watching reruns.